katie boland: writer

As a screenwriter, Boland has a prolific slate of television projects in development. She is currently packaging her next two feature films that she wrote. Her first foray into screenwriting, Long Story, Short, a web series she created and wrote based on her collection of personal essays, premiered on Hulu to millions of views. As an author, Boland’s collection of short stories, Eat Your Heart Out was chosen by leading Canadian newspaper, the Globe and Mail, as one of Three Hot Summer Reads. She also frequently writes personal essays.

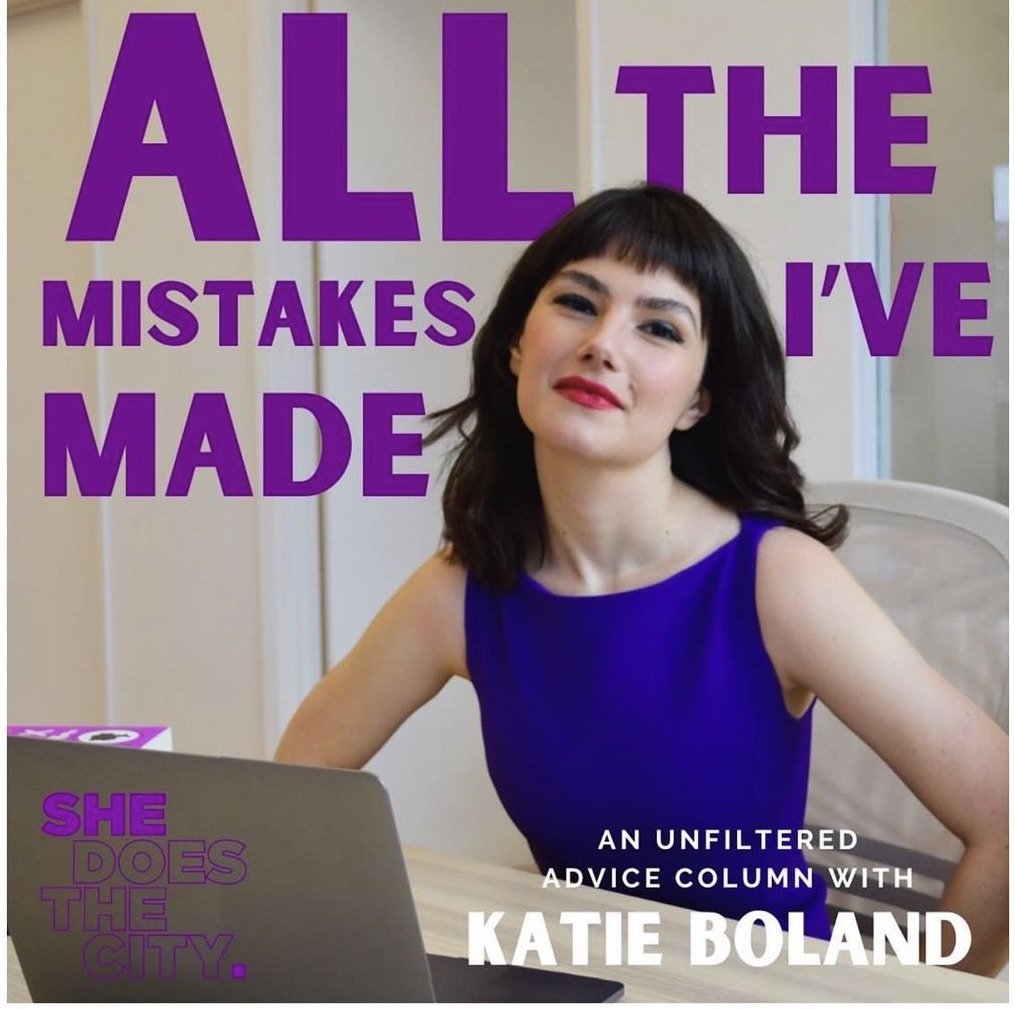

katie's monthly advice column

All The Mistakes I've Made

“Actress-turned-writer Katie Boland is a notable new voice . Eat Your Heart Out is a vibrant collection, populated by well-drawn characters who are broken but bursting with life. Largely, it’s a book of chance encounters and reunions that tackles the ways people need, help and hurt each other, intentionally and unintentionally. Reminiscent of Hemingway’s sharp minimalism, paired with Kerouac’s verve, Eat Your Heart Out tackles being alive in the here and now, with sterling writing and stellar voices.”

“A stunning debut collection. These are characters we all have known or have been, rendered with unflinching honesty but also with compassion and wit.”

“Of all her current accomplishments, I think that the new web series is perhaps the most significant. Very much like Dunham’s Girls, Katie’s Long Story, Short revolves around the shared career angst and disastrous love lives of young 20-something girlfriends finding their way in an adult world.”

“You want proof that Long Story, Short is worth the hype? How about the fact that I just watched both available episodes back-to-back and am already craving the release of the next one? Boom, addicted.”

“With her sharpshooter eye and intrepid heart, Katie Boland is the love child of Dorothy Parker and Jack Kerouac.”

“In this radiantly written collection, Katie Boland tunnels into the beating, mysterious heart of human connections. Astonishing.”

“Boland’s web series, Long Story, Short is Girls meets Toronto…one of the most entertaining and raw web series of this current summer.”

“The best new thing on the internet…a funnier, more relatable answer to HBO’s Girls.”

select personal essays

Little Yellow Pill: On Antidepressants

"It would be okay if I died right now.” I used to think that as I fell asleep at night, but not in a hungry way. I wasn’t looking at pill bottles, knives or the rope in the basement. My thoughts of dying were emotionless: I could die. That would be okay. I accepted it.

I’ve never told anyone that until now.

“Does mental illness run in your family?” the doctor asked three months ago. I sat in his office crying. I had known him since I was a child. To say out loud how I felt, to finally name it, felt disgusting.

“Yes. It does.”

“On what side?”

“Depends who you ask.”

“So both,” the doctor said after a long pause.

Bi-polar, codependency and alcoholism don’t just run in my family, they gallop. Depression, which has two of my immediate family members in a stranglehold, is something we never talk about. Mania, showing up to Christmas smelling like vodka, loving drug addicts – that’s glamorous. You can laugh about that. But what’s funny about daydreaming about death?

The doctor diagnosed me with something called Perfectly Hidden Depression.” Doesn’t that sound fake?

“If there was something wrong with your brain, of course you’d hide it perfectly,” my brother said. “That’s so you.”

Full Story here

‘Messy girls’ are all over TV, but I wish there was a series that showed what female alcoholism is really like

She’s been crying. I don’t think she’s showered in a few days. She looks exhausted and brittle, jeans sliding down her hips. She pulls at her waistband; “This is a problem,” she sighs. “I’m too skinny.”

I’m at the dry cleaner, carrying an armful of dresses to be hemmed because I’m three inches shorter than I want to be. The skinny woman keeps talking, but she doesn’t have to. With one look, I know who I’m dealing with: an alcoholic. It’s not the physical qualities, the slurring or the smell, but the evasiveness, the calculated vacancy.

“I just ran away from rehab,” she whispers. This is performance at its finest.

I tell her I am close to four years sober. She can get help if she wants to. It doesn’t really land because she’s not really here.

“Do you have Botox? Are your eyebrows real? Do you want to see pictures of my son?”

She shoves her phones at me, her baby looks around two.

“My husband gave him bangs.” I can tell she hates her husband.

Full Story here

The Fall: Katie Boland’s Journey to Recovery

“You need stitches.”

I feel cold cement beneath me. I’m sitting on a sidewalk. I look down at my dress. Why is it so bloody?

“You need stitches for your chin.”

What happened to my chin? I look down and see a rough bar napkin in my hand, pressed against the bottom half of my face. It’s soaked in blood. I can’t bite down on my left side. In a few hours, I’ll find out I broke two molars in half, too.

The man telling me I need medical attention is Australian, blonde and wearing a hat. I look at the pattern on his shirt, everything blurs. I ask the man’s name for what could be the hundredth time and forget it immediately. I don’t ask again. Even in this state, I know to pretend that we’ve experienced a mutual reality.

My mom calls. My brother calls. My boyfriend calls.

“Where are you?” they all ask.

I have no idea.

In the cab to the ER, I felt the space-time continuum shift from blacked out to sober. I’m an actress, a writer and a director. Whatever state I’m in, I think of life in scenes. Sinking into sobriety felt like when a director calls cut. You exhale. You let your face relax. You look around for some indication that you did a good job.

Instead, I saw a sliver of the cab driver in the rearview mirror. He was scared of me.

In movies, sober women are strong. Their arc is coherent. They start drunk, they struggle, they end sober. In reality, sober women are the most vulnerable adults. We wanted to disappear completely. Now, we walk around, just ourselves, with no armour at all.

Full Story here

Kent Nolan: On Death

I had just seen him the day before.

Watching the news of his death spread through that club, a crowd of young, pretty film up-and-comers that he was a part of, remains the most surreal experience of my life. Death is weird and people take ownership of it. Maybe I shouldn't be writing about Kent at all.

How do you talk about an ending this tragic, a career thwarted, a life and a person who was lost before he had even begun?

I had met Kent many times but our friendship began with us playing trampoline dodge ball. If you know me, that's weird. I hate all sports, especially group ones, but I had to go. It was at a birthday party for my friend, Kevin. The guests were a clique of cool, fiercely intelligent go-getters; mainly the cast members of a hot summer procedural that played cops who could moonlight as models.

They were a group that I wanted to be a part of. What I didn't know is that they were a group that would give me something I really needed: proof. Proof that if I was patient, there were better things ahead for me than what lay behind.

Full Story here